The Roots of Faith and the Role of Creeds

Several traits run deep in Southern American culture—faith, firearms, and food. Among these, faith stands out as a defining thread woven into the very fabric of the South. It’s no surprise that a church can be found on nearly every corner. One might pass a Methodist church here, a Presbyterian church there, and a Baptist or Pentecostal congregation just down the road.

Yet for the sincere believer, a natural question arises: “How am I to know what each of these churches believe?”

You might ask a pastor, “What does your church believe?” to which the confident reply often comes, “Oh, we believe the Bible, of course!” A response that—rightly—should be true of any Christ-exalting, Bible-believing church. But such an answer invites further reflection:

- What does this local church believe about the Bible?

- How does it understand doctrines such as soteriology, ecclesiology, missiology, and eschatology?

- How does it approach Scripture, leadership, and worship?

- What truths does it proclaim about who Christ is and what God has done?

These are not new questions. Throughout history, believers have wrestled with them—sometimes passionately, sometimes divisively. From the earliest centuries, differing interpretations of Scripture (some faithful, others heretical) have compelled the Church to clarify and defend biblical truth. This effort gave birth to the great creeds and confessions of the faith.

Before we trace that history, it’s helpful to define our terms.

A church’s confession or catechism expresses what it believes—often structured in a question-and-answer format.

For example:

Q: What is the chief end of man?

A: Man’s chief end is to glorify God and to enjoy Him forever.

(Westminster Shorter Catechism, Q1; cf. 1 Corinthians 10:31)

A creed, on the other hand, declares in Whom we believe. For example: “My creed is Christ and Him crucified.”

These words—creed, confession, and catechism—are closely related, and I may use them interchangeably. Yet it’s vital to remember this: none of these stand above Scripture. The Bible alone is God’s authoritative, infallible Word. These tools simply serve as faithful summaries of biblical truth—meant to bring clarity to God’s Word and unity to His Church.

So with that foundation laid, let’s rewind the tape and trace the path that led to the creeds and confessions Christians hold dear today.

The Three Great Creeds of the Christian Church

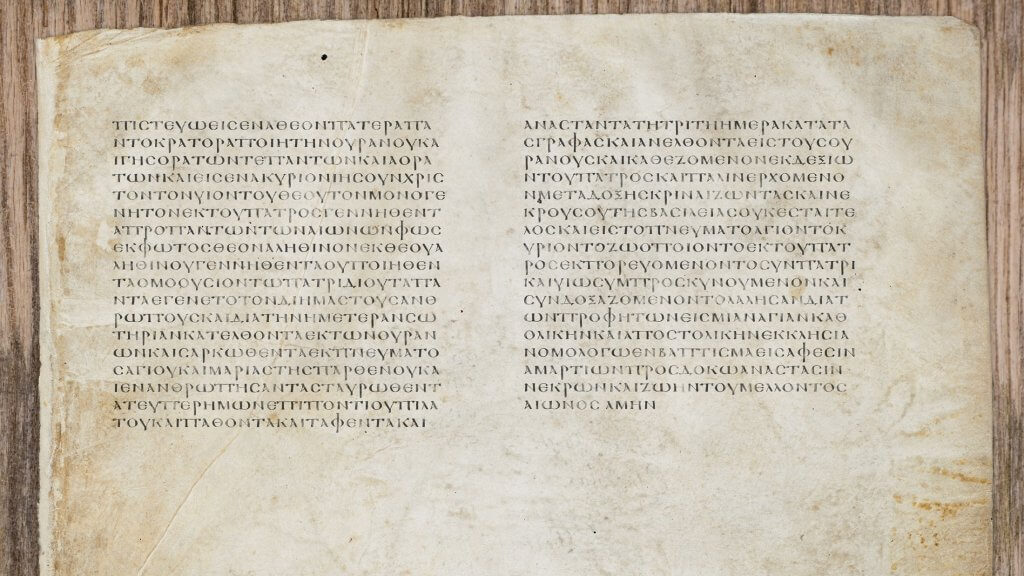

Historically, the Christian Church has united around three primary ecumenical creeds: the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Athanasian Creed.

The Apostles’ Creed

The origins of the Apostles’ Creed are veiled in mystery. Its exact author is unknown, and no definitive record explains how this first-person statement of faith came to be. Nevertheless, it remains the most widely recognized post-biblical creed in Christian history. Many believers have recited it in congregational worship, perhaps without realizing the depth of theology it holds or its influence upon later confessions of faith.

In many ways, the Apostles’ Creed serves as the foundation upon which other historic confessions are built. John Calvin, in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, wrote that the Creed “furnishes us with a full and every way complete summary of faith, containing nothing but what has been derived from the infallible word of God” (2.16.8). More recently, Dr. Brian Hanson of Bethlehem College & Seminary has noted that “the Creed, also known as the Twelve Articles of Faith, expresses essential biblical doctrines that have been articulated, defended, and embraced for nearly two thousand years of church history.”

Its enduring impact is evident in later confessional documents. The Belgic Confession of 1561, the official doctrinal statement of the Dutch Reformed Church, references the Apostles’ Creed as one of the historic creeds “we willingly accept” (Article 9). Similarly, English theologian Richard Baxter—often called “the chief of English Protestant schoolmen”—encouraged pastors to lead their congregations in reciting the Creed during the sacraments of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper. His purpose, as he wrote in The Christian Religion Expressed, was to help believers “declare what doctrine it is that we assemble to profess, and to preserve it in the minds of all.”

Baxter’s use of the Creed demonstrates its liturgical and unifying role in the Church—an expression of shared doctrine that bound believers together across generations.

The Nicene Creed: Clarity Amid Controversy

Several centuries later came the Nicene Creed, officially adopted at the Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325 and later affirmed at the Council of Constantinople in 381. Unlike the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed was a product of an ecumenical council and was declared binding for the whole Church.

Building upon the framework of the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed offered a fuller and more theologically precise explanation of the essential doctrines of the Christian faith. Dr. Kevin DeYoung, professor at Reformed Theological Seminary in Charlotte, describes the Nicene Creed as being “more theologically precise” than its predecessor—particularly in its articulation of Christ’s divine nature.

The council at Nicaea convened to address a serious theological crisis: the Arian heresy, taught by the Alexandrian elder Arius, who claimed that Christ was a created being—exalted, but not divine. This denial of Christ’s full deity threatened the very heart of the gospel. In response, the Council of Nicaea proclaimed with clarity the biblical truth of Christ’s divinity, affirming that the Son is of the same substance (homoousios) as the Father.

In doing so, the council established orthodoxy concerning the Hypostatic Union and the Trinity—the equality of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Church echoed the declaration of the Apostle Paul, who called Jesus “our great God and Savior” (Titus 2:13). The council’s decision marked a monumental step in the Church’s ongoing pursuit of faithfulness to the Word of God.

The Athanasian Creed: Precision in Trinitarian Doctrine

The third of the major ecumenical creeds, the Athanasian Creed, bears the name of Athanasius of Alexandria—a staunch defender of Trinitarian orthodoxy and one of the fiercest opponents of Arianism. While Athanasius himself likely did not write the creed, his influence upon it is unmistakable.

Dr. R.C. Sproul observed that although Athanasius was not the author of the Nicene Creed, “he was its chief champion against the heretics who followed Arius, who argued that Christ was an exalted creature but less than God.” Upon Athanasius’s death in A.D. 373, his tomb bore the epitaph: “Athanasius contra mundum”—“Athanasius against the world.” History remembers him as one who stood firm for biblical truth, even when it meant standing alone.

The Athanasian Creed expands upon the work of Nicaea, offering a detailed and unambiguous exposition of the Godhead and of Christ’s two natures. It was written, at least in part, to combat the monophysite heresy of the fifth century, which claimed that Christ possessed only one, blended nature—neither fully divine nor fully human.

The Council of Chalcedon in 451 addressed and condemned this teaching, and the Athanasian Creed reflects the council’s conclusions. As Dr. Sproul summarized:

“The Athanasian standards examined the incarnation of Jesus and affirmed that in the mystery of the incarnation the divine nature did not mutate or change into a human nature, but rather the immutable divine nature took upon itself a human nature.”

Though never ecumenically adopted like the previous two, the Athanasian Creed remains a remarkable testimony to doctrinal fidelity. Its precision in articulating the mystery of the Trinity and the incarnation continues to serve as a safeguard for orthodoxy.

Why the Creeds Still Matter

While the three great creeds differ in emphasis and historical context, they share one aim—to preserve and proclaim the truth of Scripture in the face of error. Each arose from the Church’s determination to remain faithful to the Word of God and to provide believers with a clear, unified confession of faith.

The Necessity and Function of Creeds

Their Necessity

The need for biblically faithful creeds within our local churches has never been more urgent. As our society continues to drift deeper into postmodernity, secularism, and what can rightly be called a post-Christian Western world, truth itself has become unstable at best—and under assault at worst.

If we believe the Bible to be true, then it is essential that we also know what we believe about the Bible. I’ve previously heard the well-meaning statement:

“We don’t believe in the words of man found in the creeds—we believe the words of God found in the Bible!”

At its core, this is a devout affirmation of Scripture’s sufficiency, and I agree with that conviction. Yet this is precisely where precision becomes vital. If Scripture alone is our supreme authority, then we must be able to clearly articulate how and what we believe about it.

Many groups claim to “believe the Bible”—Catholics, Episcopalians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Oneness Pentecostals, and others. Yet, as history and doctrine reveal, their interpretations of the Bible differ widely. Some of these groups remain within the bounds of Christian orthodoxy, while others have strayed so far that they can only be identified as false gospels or theological cults.

This diversity of belief underscores the Church’s need for clarity. The importance of declaring, with precision, what Scripture teaches about who Jesus is, how salvation is accomplished, and the nature of the Holy Trinity cannot be overstated. Sadly, the modern Church has often understated the importance of creeds in the life of the congregation.

Dr. Carl Trueman, author of The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, Strange New World, and Crisis of Confidence, warns of a concerning trend within contemporary evangelicalism—a hesitancy to define and defend doctrinal boundaries. He writes:

“Churches need statements of faith that do more than specify ten or twelve basic points of doctrine. They need confessions that seek to present in concise form the salient points of the whole counsel of God. And I am convinced that the section of the church most cautious about creeds and confessions—Protestant evangelicalism—could actually best protect what it values most (the supreme authority of Scripture) by, perhaps counterintuitively, embracing the very principles of confessionalism about which it is so cautious.”

Trueman’s insight is crucial. Where there was once unity and clarity regarding the inerrancy, infallibility, and divine inspiration of Scripture, questions now abound—even within the Church—about the relevance of Scripture, the deity of Christ, and moral absolutes. The Reformation doctrine of Sola Scriptura—that Scripture alone is authoritative for faith and practice—has, in some circles, been reduced to a secondary or assumed truth rather than the bedrock of Christian conviction.

Now, perhaps more than ever, the Church must recover the creedal and confessional clarity that has historically safeguarded biblical orthodoxy.

Their Function

Creeds serve two indispensable functions within the local church—each acting as a theological and doctrinal guardrail.

First, creeds confront the rise of subjectivism that now permeates much of evangelical Christianity. In a culture where truth is treated as fluid and personal, creeds stand as bold affirmations of objective reality. Consider the question: Is there much left that society still regards as objective truth?

- The media? No.

- Science and biology? Increasingly, no.

- History? Even that is often rewritten.

- The Gospel truth and how it is proclaimed? That, too, is under scrutiny.

How the Church answers this last question will shape its future witness. Creeds serve as immovable markers—declaring that truth is not ours to invent but God’s to reveal.

Second, creeds articulate profound theological truths in a form that is both faithful to Scripture and accessible to the believer. They provide concise, collective summaries of doctrine that help the Church think, worship, and live rightly before God.

Carl Trueman continues his defense of the historic creeds with this insight:

“Creeds and confessions do not negate what is true about expressive individualism but, when used correctly, answer the deepest legitimate concerns of the same.”

In other words, the creeds remind us that while our faith is personal, it is never private or self-defined. They tether us to history—to the communion of saints who have confessed these same truths through centuries of trial, persecution, and reform.

For many modern believers, creeds have become relics of a bygone era—dusty artifacts of church history. Yet now is precisely the time to recover them. To embrace the creeds is not to elevate human tradition above Scripture, but to affirm Scripture’s truth in unity with the faithful who have gone before us.

Creeds are comprehensive, historic declarations of faith, agreed upon by councils or congregations, that clearly, concisely, and collectively express how the Church understands and applies the Word of God. They are not merely ancient words to recite—but enduring truths to believe, confess, and live by.

Recommended Resources

A Crisis of Confidence: Reclaiming the Historic Faith in a Culture Consumed with Individualism and Identity

From the Book’s Description: Carl Trueman analyzes how ancient creeds and confessions protect and promote Biblical Christianity in a culture of expressive individualism. Historic statements of faith―such as the Heidelberg Catechism, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Westminster Confession of Faith―have helped the Christian church articulate and adhere to God’s truth for centuries. However, many modern evangelicals reject these historic documents and the practices of catechesis, proclaiming their commitment to “no creed but the Bible.” And yet, in today’s rapidly changing culture, ancient liturgical tradition is not only biblical―it’s essential.

Find your copy of this book on Amazon.

The 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith

Check out this confession in an organized and easy to navigate website. Click here.

The Westminster Confession of Faith

Check out this link from Ligonier Ministries.

The New City Catechism App

This free app pairs each question and answer with a Scripture reading from the ESV, a short prayer, and a devotional commentary written by contemporary pastors, including John Piper, Timothy Keller, and Kevin DeYoung, and historical figures, such as Augustine, John Calvin, Martin Luther, and many others.

Leave a comment